Film Review #187: All About Lily Chou-Chou

The Lost Youth and Digital Loneliness of

All About Lily Chou-Chou

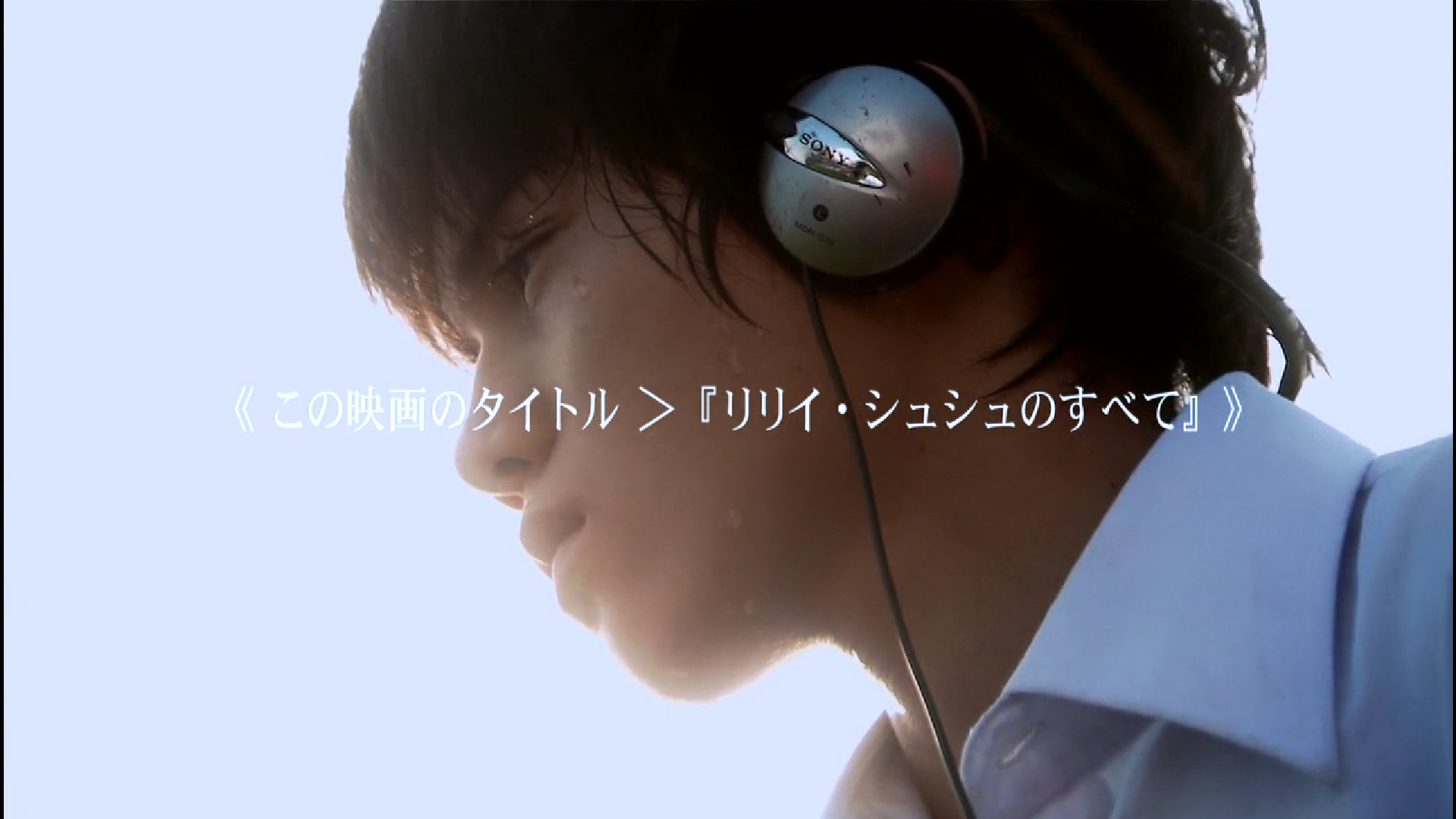

The film opens on a void – digital hieroglyphics spasming into Japanese characters glowing against a black backdrop. It introduces our enigmatic Lily Chou-chou: a fictional alt-pop singer channelling Björk’s electro-eclecticism and Faye Wong’s dreaminess, and her mythical force, the “Ether”. The image then flickers to the film’s most famous visual: Yuichi stands hunched over his analogue Discman, swallowed by verdant paddyfields.

These sprawling countrysides, repeatedly interrupted by the flickering forum posts of Lily’s online fangroup, “Lilyholic”, create a strange, yet oddly harmonic visual grammar. This hybridised cinematic space is where All About Lily Chou-chou resides: where connection and loneliness coexist, and freedom turns into imprisonment. Iwai’s refusal of these binaries renders the teenage experience a stubbornly liminal and desperate one, suspended between Japan’s Lost Decade and the uncertainty of a nascent digital world.

Teenagehood in Japan’s Lost Decade

Set in the late-1990s to early-2000s, Lily Chou-chou takes place in Japan’s “Lost Decade” – an era following the bursting of the country’s bubble economy in 1991. Amidst mass social turmoil, Japan’s youth bore the brunt of this collapse: with scarce employment opportunities and a “pressure cooker” education system, their disillusionment led to a rise in youth delinquency.

Iwai never makes explicit reference to this context, yet the tonal unease pervades. Televisions drone on in the background, reporting bus hijacking incidents. A customer of Yuichi’s mother’s hair salon sighs: “Kids these days are very scary.”

Liminality and hybridity

The social turmoil of the Lost Decade coincides with another era of flux: the turn of the century and the dawn of the internet. Iwai’s engagement with this transition not only gives Lily Chou-chou its trademark analogue aesthetic but symbolises the transitory void between childhood and adulthood.

Shot on a Sony HDW-F900 – a camera digital in medium, yet engineered to retain the traditional 35mm film look – infuses the film’s very look with a sense of transitionality. Further hybridising the dichotomy of the modern and the traditional is Iwai’s juxtaposition of the natural and digital world. The sprawling paddyfields of Japan are routinely extinguished by the black screens of the ‘Lilyholic’ chatroom, where messages flicker over the screen, before the paddies take over again. A similar hybridity occurs as the starkly contrasting classical arpeggios of Debussy and the grungy alt-rock of Lily Chou-chou are interplayed throughout the film, capturing the precarious digital transformation and its liminality in the film’s very soundscape.

Two narratives unfold simultaneously: one of the reticent Yuichi in the physical world, and one of his passionate online forum persona, Philia. Lukas Heller argues that this “establishes Yuichi in a state of in-betweenness – of being two people in two places at once”; even in their identity, these teenagers occupy a state of hybridity.

Through a shifting assemblage of media and a non-linear narrative, the film also mirrors the fragmented subjectivity of its teenage characters’ minds. While ostensibly overwrought, its visual language – jump cuts, Dutch angles, abrasive close-ups, handheld shots, and frames drenched in overexposure – is unexpectedly coherent in its capturing of uncertainty.

Together, the film’s hybridity and instability plunge its characters into a disorienting, liminal reality. It transforms teenagehood into an experience not to be deciphered, but felt in all its peculiarity.

Freedom and imprisonment

The teenagers seek refuge in what they call the “Ether”, a term used by fans of Lily Chou-chou to describe the freeing, transcendental substance found in her music. The singer is transformed into an almost divine being, and her music a spiritual sanctuary in what Yuichi calls the “Age of Grey”. Beyond functioning as a cautionary message on toxic fan culture – something that would become more pronounced in Japan in later years – this stages a deceptively simple polarity between the two states of being, hailing the Ether as the cure-all for their alienation.

While this polarity is rarely contested in interpretations, the Ether ultimately feels equally alienating. Within Lilyholic, Yuichi, under his username ‘Philia’, shares his closest friendship with an anonymous ‘Blue Cat’, exchanging intimate confessions conspicuously under the veil of the internet. Yet, this online refuge and community thus feels illusory: the forum posts are isolated on dark, empty screens, as if they are ultimately speaking into a void.

Watching the film, the hollow loneliness of the digital abyss felt more familiar than ever. Often coined “digital loneliness”, this phenomenon would resonate strongly with the youth of our screen-mediated world, where frequent internet communication likely intensifies, rather than assuages loneliness. Even in 2001, Iwai captured this feeling of being simultaneously connected and alone with a prescient complexity I have never seen represented in cinema before. Like the hybridisation of modernity and tradition, Iwai deconstructs the polarity of isolation and community, allowing teenagehood to occupy a liminal space between the two.

Outside these digital spaces, the characters become even lonelier. The dream-like, overexposure swiftly morphs from a sanctuary into a prison: the backlight hits characters, drawing a halo that visually isolates their figures from the rest of the frame, imprisoning them. Characters are often framed alone or positioned sparsely within the frame, such that intimacy is rarely ever an occurrence.

As the soaring arpeggios of Debussy’s Arabesque No. 1 and the freeing riffs of Lily Chou-chou’s rock take over the auditory landscape, physical loneliness takes on an almost ethereal quality – such scenes almost become an escape. Yet, the reality of their isolation simultaneously suffocates us.

Desperation and violence

Under a veneer of dreaminess, All About Lily Chou-chou also hides alarming violence in its narrative. The brutality the teenagers enact, both unto others and themselves, is the culmination of their desperation and loneliness, translating into broader societal implications.

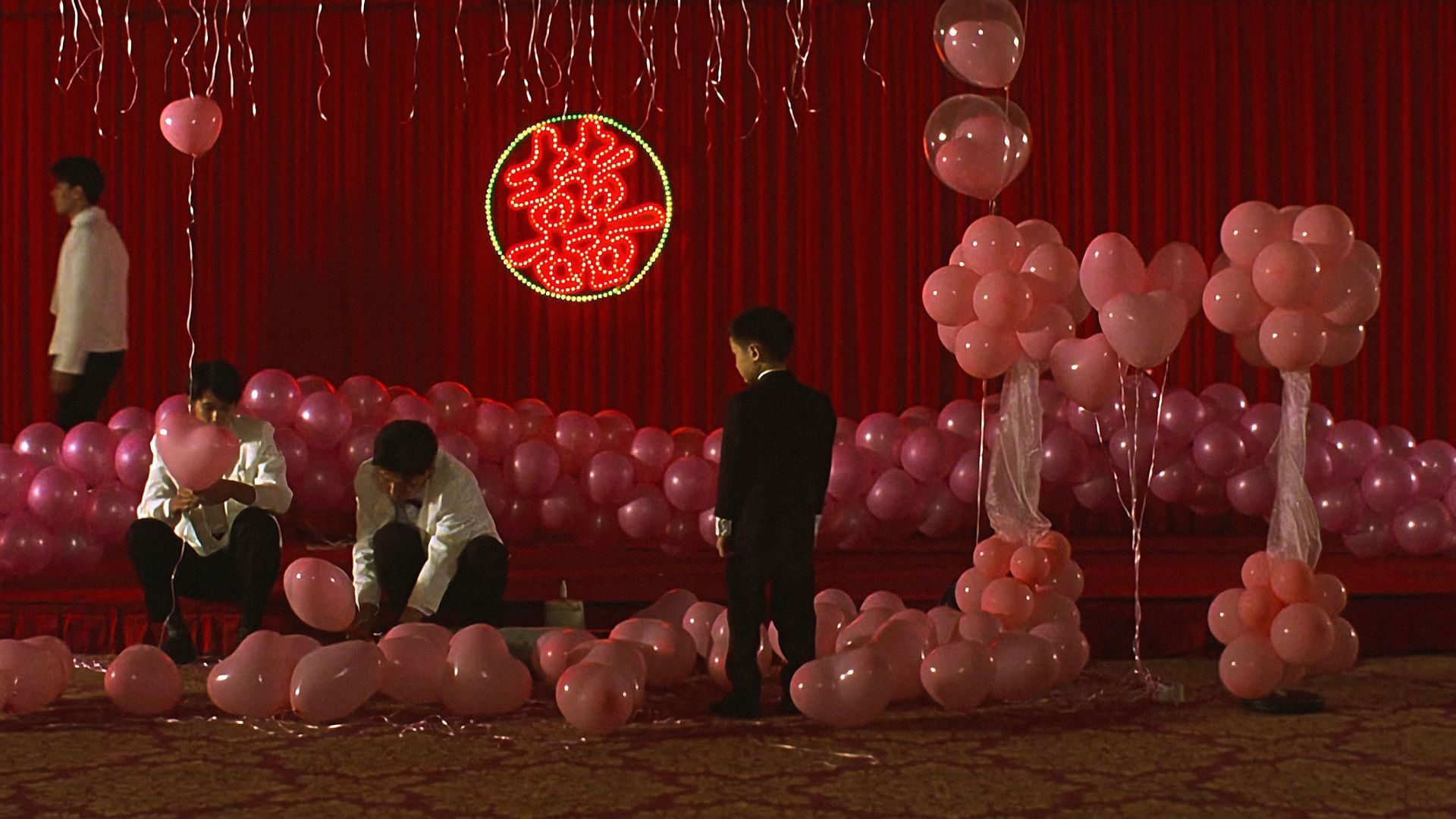

The Ether, a presumed cure to alienation, seems instead to accompany many of these teenagers in their acts of violence. Tsuda, a schoolmate of Yuichi’s who is blackmailed into prostitution by Hoshino, with the help of an exploited and bullied Yuichi under him, is introduced to Lily Chou-chou’s music by Yuichi. Iwai intercuts shots of the three of them, all with headphones on and Lily’s music in the background. Their anonymous forum posts are overlain onto the screen – Yuichi confesses his desperation, “I wanted to die… But I couldn’t,” to which Hoshini responds, “I know the pain you feel,” talking him out of the act. Momentarily, catharsis and comfort seem tangible.

However, the irony remains: after all, these three characters have hurt each other. After Tsuda seemed momentarily free in the Ether, flying kites, the film cruelly cuts to a shot of her lifeless body, thrown off a cell tower. The teenagers’ momentary escape turns back into imprisonment. The Ether could not save them.

The climactic act of violence in the film takes place near the end: the online personas of Yuichi and Hoshino promise to meet at the Lily Chou-chou concert. All hopes subvert when Yuichi realises Blue Cat is Hoshino all along. After Hoshino tears Yuichi’s ticket, Yuichi snaps, fatally stabbing him once the concert ends. Any possibility of a digital connection consummated in reality is cruelly denied.

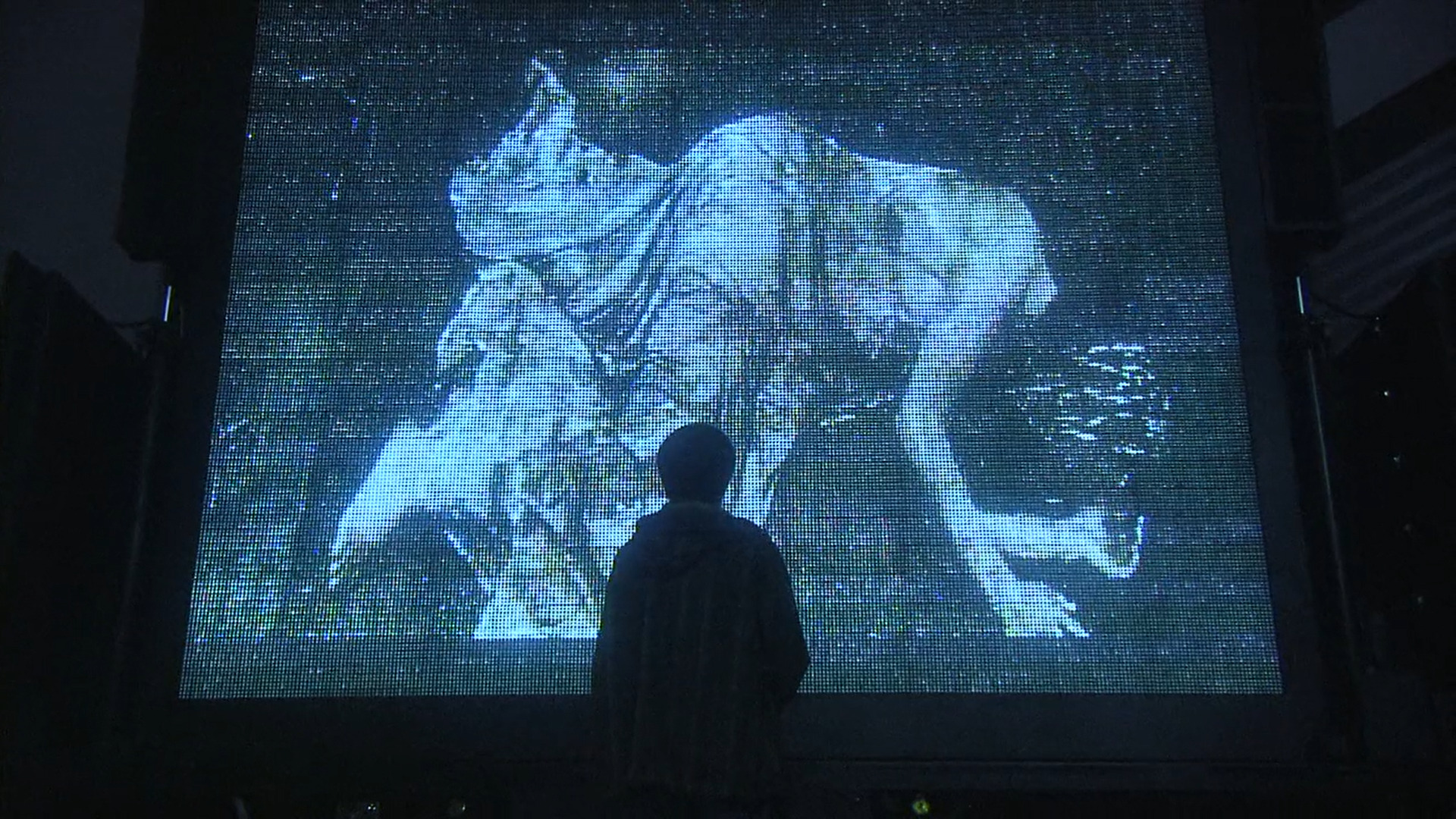

As Yuichi stands alone, engulfed in cold blue by an LED screen of Lily Chou-chou while her live music rumbles on inside the stadium, the Ether becomes the most imprisoning of all realities. The final denouement of the narrative brings together Yuichi’s two worlds and traps him in an in-between, where every attempt to seek connection and the Ether leaves him with nothing at all.

An unsettling mirror

Teenagehood for Iwai is a tightrope between childhood and adulthood, isolation and community, freedom and imprisonment – a state of endless liminality. In this void of adolescence, it seems the loneliest experiences occur when we are caught in between binaries. In an era where technology has become the very fabric of society, All About Lily Chou-chou’s haunting portrait of adolescence is perhaps more relevant now than ever. Yet, to the phenomenon of digital loneliness, the film presents no easy answer. It only holds up a mirror to our society, a cry of desperation captured in a film.

---------------------

About the author: Kaela lives two lives – in one, she is on a constant quest to make and consume art, and can be found writing, reading, photographing, playing music, and documenting the world around her. In her second life, she enjoys advocating for social and environmental justice, and hopes to combine the two to bring about a little more understanding in the world.

This review is published as part of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme, with support from Singapore Film Society.