Film Review #186: Yi Yi

Seeing from a Distance: Modern Life through

Edward Yang’s Lens inYi Yi

In Yi Yi (2000), Edward Yang’s three-hour-long multi-generational epic, we follow the middle-class Jian family as they navigate love, loss, and their search for identity in modern Taipei. Father NJ (Wu Nien-Jen) faces business troubles and a rekindled love; daughter Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee) copes with guilt and the joys and hurts of first love; and son Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang) pursues life’s truths amidst relatable childhood struggles. Yang’s final masterpiece, so nostalgic and full of life, extensively explores urban ennui, where each character quietly grapples with their personal discontents. These everyday struggles are mirrored in Yang’s restrained and purposeful direction, allowing the film’s themes to unfold through its visual composition and Yang’s stylistic choices.

One of the most striking ways this comes through for me is Yang’s frequent use of off-centre compositions. Characters are often pushed to the side of the frame, surrounded by negative space or swallowed up by the city. We see them, at the edge of the screen, walking along the streets of Taipei or reflected in windows, faces blending with neon city lights and passing traffic. This visual displacement renders these characters small and seemingly insignificant against the vastness of the urban landscape, emphasizing the solitude and disconnection they carry within. It marks the quiet distance between the characters and their surroundings, from one another, and even from themselves.

This directorial choice, when employed in tandem with static and long-distance shots, further underscores the film’s focus on emotional isolation in modern urban life. By positioning characters away from the centre of the frame and allowing multiple actions to unfold simultaneously within a single, unmoving shot, Yang prompts viewers to observe the characters within their full environment, rather than designating a singular focal point. In doing so, the audience is encouraged to actively scan the image in order to glean the full context of the characters’ experiences, mirroring their own attempts and struggles to locate meaning within the complexity of their lives.

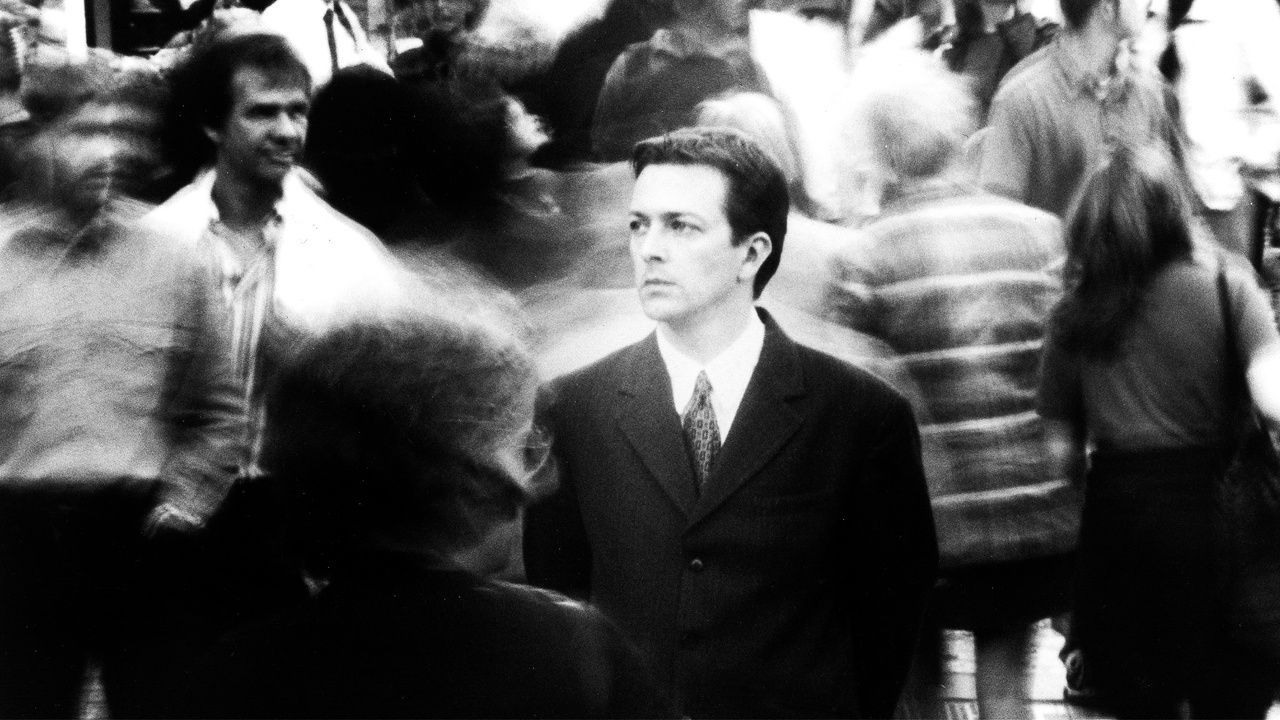

Yang’s use of this combination of techniques is especially evident in his depiction of NJ in the workplace, with a clear example occurring in the scene captured above. NJ is shot through glass doors, positioned in the foreground to the right of the frame, while his three coworkers converse together in the background on the left. This spatial division within the frame highlights his literal and figurative separation from his colleagues, visually emphasising his alienation and sense of insignificance within his professional environment and, as the film gradually reveals, within society at large. Through the repeated utilisation of such compositions, Yang’s direction consistently echoes Yi Yi’s broader themes of loneliness, dissatisfaction, and a persistent longing for connection.

Another aspect of Yang’s direction that resonated with me personally is his use of frame-within-a-frame compositions, which subtly reinforces the film’s central themes of alienation and introspection. Characters are often precisely positioned within doorways, windows, mirrors, or even urban structures, creating layered frames that guide the viewer’s eyes while adding visual depth. These framed compositions create a sense of distance for the audience, positioning them as quiet observers, almost intruding upon intimate, everyday moments of these characters. This observational quality aligns with Yi Yi’s slice-of-life approach, allowing ordinary experiences to feel universal and relatable, while still hinting at the characters’ emotional solitude.

Notably, these frames do not merely organise space. They enclose the characters, isolating them from one another and from the world around them. These characters are visually confined within architectural boundaries, just as they are trapped and held back by their own internal struggles, suggesting a deeper emotional restraint that corresponds with their inability to fully articulate their feelings of guilt, regret, and desire. This is especially evident in scenes involving NJ and Ting-Ting, who are repeatedly framed through windows, mirrors, or doorways during moments of quiet reflection, underscoring their emotional distance from others even as they are physically present. The use of mirrors provides further nuance by introducing double images, drawing parallels with the film’s preoccupation with self-examination and inner conflict, and ultimately reinforcing the emotional isolation central to the essence of these characters.

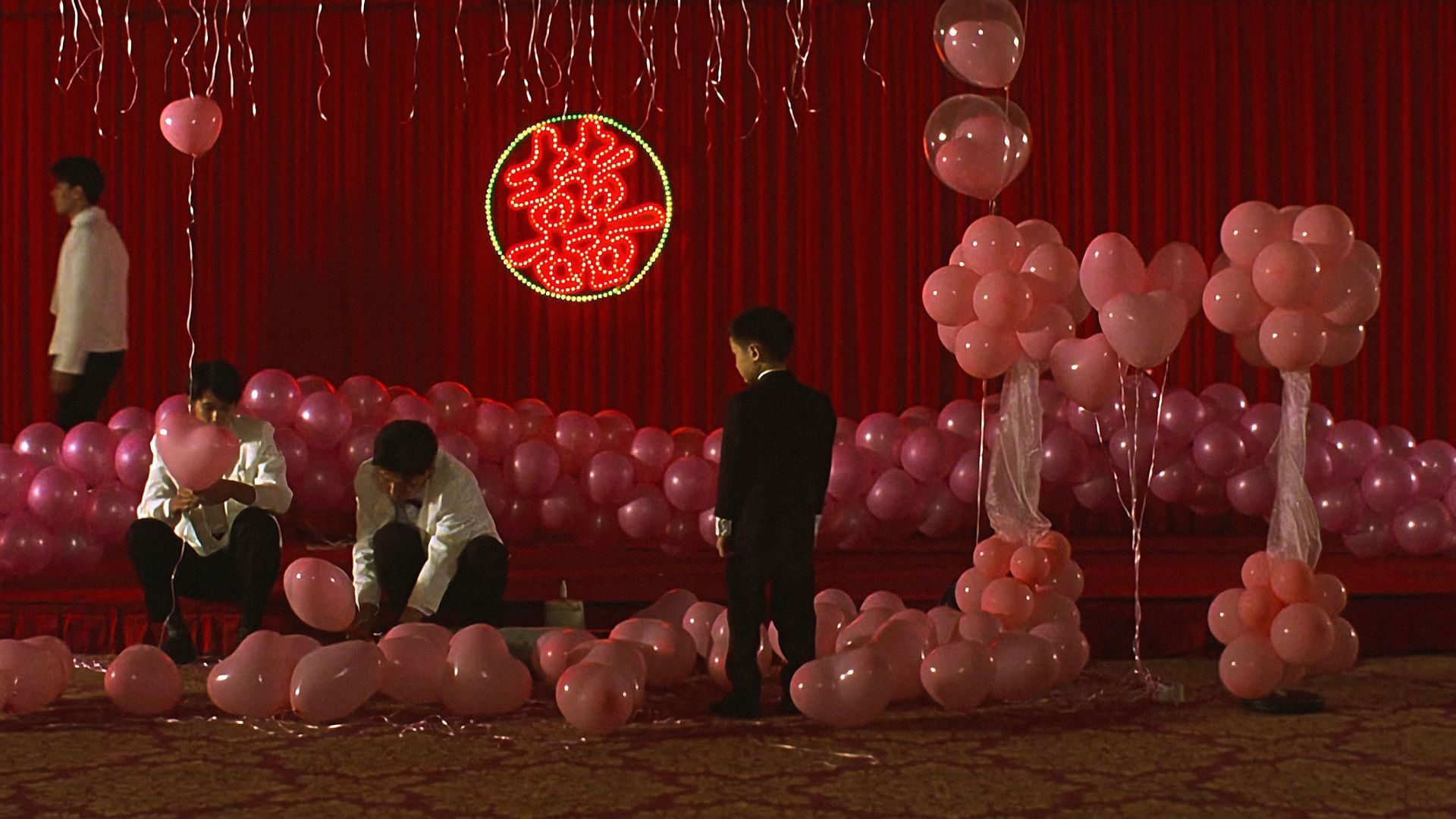

Ultimately, while Yi Yi captures feelings of alienation and inner turmoil, so often emphasised through Yang’s direction, it is equally a film about connection, and about how we are often more alike than we realise. Rather than resolving this tension, Yang allows both states to coexist, embedding it into the very structure of the film. Yi Yi opens with a wedding and closes with a funeral, framing life as cyclical rather than linear, where love, heartbreak, solitude, marriage, new beginnings, and death exist side by side. Through this, Yang reminds us that life is inherently messy. We are all, in some ways, learning to live for the first time, and the film urges us through Mr Ota (Issey Ogata) to not fear these “first times”, even when the path forward feels lonely or uncertain.

At the same time,

Yi Yi

remains attentive to the limits of individual perspective. Yang acknowledges that navigating life’s complexities can feel isolating, especially as it seems we only ever understand fragments and never complete truths. Yet, in suggesting that no one can see the whole picture alone, the film offers its viewers hope, articulated most clearly through Yang-Yang. Perhaps sometimes all we need in our lives is a Yang-Yang, someone who will take a picture of the back of our heads, show us what we cannot see, tell us what we do not know, and offer us the other half of the truth. Someone who will show us the world through another’s eyes, and fill in the gaps in our own sketches of the world.

Yi Yi

is a quiet meditation on empathy, and a gentle reminder that cinema, too, can bridge these gaps, helping us better understand not only one another and ourselves, but also the world we share.

The next screening of the film’s 25th anniversary 4K digital restoration will be held on 25 January at Oldham Theatre.

---------------------

About the author: Jing’s morning ritual includes refreshing Letterboxd and catching up with the latest reviews. With an intense and ever-growing passion for film, Jing believes deeply in the beauty and importance of the movie-going experience and hopes to spread the joy of cinema to a wider audience. When not watching films, Jing enjoys reading and watching football (visca el Barça!). Jing is always excited to meet and connect with fellow film lovers, and can be found on Instagram at: @_j.img_

This review is published as part of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme, with support from Singapore Film Society.