MINDS Film Festival 2023: An Interview with Jerry Rothwell

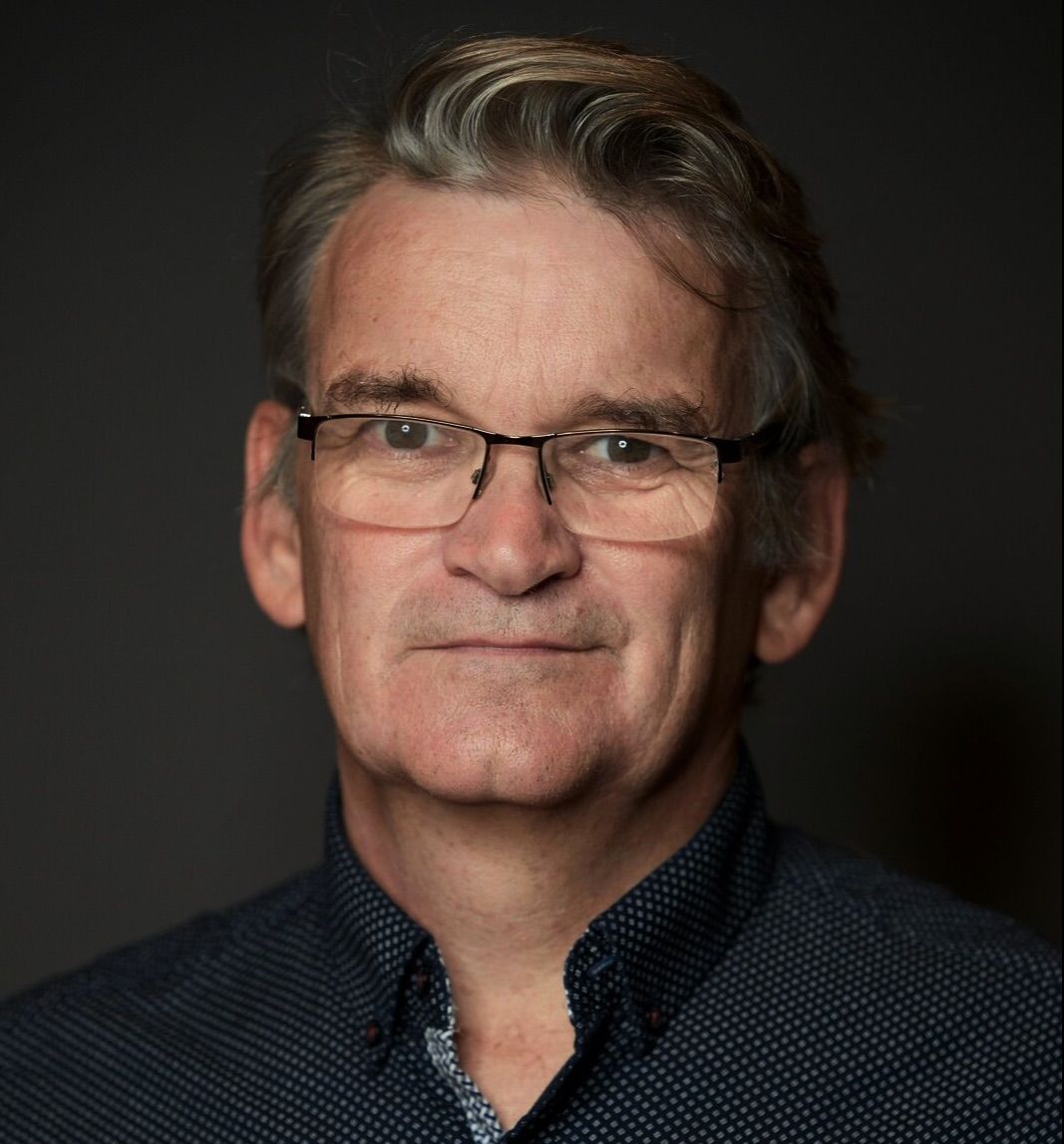

Credits: jerryrothwell.com

Director's Statement

Naoki Higashida’s descriptions of a world without speech provoke us to think differently about autism. For most of history, nonspeaking autistic people have been considered less than human: ostracized within communities, banished to institutions, even in some ages and places, killed en masse. Stigma is still a feature of most autistic people’s lives.

But Naoki’s evocative descriptions of the maelstrom of thoughts, feelings, impulses and memories which affect his every actions lead us, as David Mitchell writes in his introduction to The Reason I Jump, to understand that “inside the… autistic body is a mind as curious, subtle and complex as any.” Naoki debunks the ideas often held about the autistic spectrum — that at one end there are geniuses and at the other fools. Instead he describes a magnificent constellation of different ways of experiencing reality, which for the most part, are filtered out by the neurotypical world.

For a filmmaker, this offers an opportunity to use the full potential of cinema to evoke these intense sensory worlds in which meaning is made through sounds, pictures and associations, as well as words. While no film can replicate human experience, my hope is that THE REASON I JUMP can encourage an audience into thinking about autism from the inside, recognizing other ways of sensing the world, both beautiful and disorientating. I hope the film takes audiences on a journey through different experiences of autism, leaving a strong sense of how the world needs to change to become fully inclusive.

– JERRY ROTHWELL, 2019

Director Q&A

Film Still from THE REASON I JUMP

Why was making this film important to you?

The idea for the film came from producers Stevie Lee and Jeremy Dear, who are the parents of an autistic teenager (Joss, who is in the film). They had read Naoki Higashida’s book The Reason I Jump which had transformed their understanding of their son and they wanted to make it into a film.

When I was approached to direct it, I felt a strong affinity with the project. Autism has been very much a part of my life - both in my extended family and in my work. Back in the ‘90s I set up participatory media projects focused on disability rights and self-advocacy by people with learning disabilities - and my film Heavy Load in 2008 (also produced by Al Morrow) was about a punk band some of whom were autistic. I’ve always been disturbed by society’s response to nonspeaking autistic people - who are constantly underestimated with labels like ‘severe’ and ‘low functioning’ which, as well as being misleading about people’s capacity to think and understand, also indicates a kind of hopelessness which increases marginalisation.

When I first read Naoki’s book it took me by surprise. So fluent and perceptive was the writing of this teenager that I - like some of Naoki’s reviewers - wondered how much his original words had changed through the process of transcription and translation. It certainly ran against the established idea that autistic people lack a ‘theory of mind’, something that had never matched with my experience anyway. Meeting Naoki was revelatory too. His capacity to use his alphabet board unaided to type thoughtful answers to my questions - whilst at the same time being subject to distractions, impulses, and apparently random associations, was extraordinary to observe. During our conversation he would repeatedly stand up and go to the window before sitting down again to type the remainder of whatever sentence it was that had been interrupted by this impulse. When I asked him what it was that drew him to the window, he typed “I watch the wheels of cars”. When I asked why, he typed “They are like galaxies rotating”. Think of that, next time you’re waiting for a bus.

Once you recognise the capacities of nonspeaking autistic people and how they have been systematically overlooked, then our terrible history - of institutionalisation, behaviour modification, killings - becomes all the more shocking. I hope the film can play a role in changing those misconceptions. The idea of neurodiversity - that we all perceive the world in subtly different ways - is a powerful and important one, which I think helps build the bridges and solidarity we need for a more inclusive world.

What were the challenges and opportunities of using Naoki’s ground-breaking book as a foundation for the film?

In previous documentaries, I’ve tended to adopt a method which first finds a shape for the film and then looks for narrative in whatever situation I’m filming, gradually building a more and more detailed structure through the production process.

But the book The Reason I Jump is organised as answers to a set of 58 questions about autism. It has no plot and few characters other than Naoki and his family. It’s beautifully written, but initially the idea of turning it into a film felt quite daunting - especially as the option of making the film about Naoki wasn’t available, because Naoki didn’t want to appear on screen; he wanted his writing to stand for itself.

So the film takes the book as a starting point and riffs on its themes and ideas. In the end, this became a strength and led perhaps to a more unusual film than an issue-led biopic. It felt to me that the film’s structure should be a developing revelation of Naoki’s ideas about autism whilst immersing us in the everyday experiences of other nonspeaking autistic people in different parts of the world. Naoki’s words apply to himself - and as he says himself, he can’t claim to speak for all autistic people - but they do provide a nudge to think about the things we’re seeing on screen in a different way.

Not having a single story was a first for me - and really changed the production process. This process felt much more instinctive and responsive to the immediacy of whatever we were filming. There were plenty of dead ends, but as we developed the film a shape emerged: one which took an audience from an intense visual and auditory world to one of sensory overload through to finding a way to communicate, and to fighting stigma. I thought it was important to explore experiences of autism in the global south and so sought out contributors in Africa and India as well as the US and UK and, rather than intercut their stories, I gave them each a section where we can spend time with and get to know them.

Can you tell us about the research process?

Our research took us into the literature of brilliant writing by other nonspeaking autistics - Tito Mukhopadjyay, Ido Kedar, Amy Sequenzia - and also to first-hand accounts about sensory experience from other autistic writers - such as Donna Williams’ Autism and Sensing and Temple Grandin’s Thinking in Pictures. There are common themes to this writing - describing a world in which removing the neurotypical filters points us towards aspects of human experience that many of us only half sense. Those ideas are echoed in some of the neuroscience around autism - and we spoke to Prof. Henry Markram about his ‘Intense World’ theory and looked at research around language and motor-sensory issues. We tried to build as neurodiverse a production team as we could - and also drew on an advisory group of autistic people who were incredibly supportive and helpfully provocative at key moments.

Tell us a little bit about the concept of having the Japanese boy journey through different landscapes?

It felt to me important that when Naoki wrote the book he was only 12 or 13, and that much of what he writes about is his experience of being an even younger child - the beginnings of his awareness of difference, of his autism, of himself and the judgements of others. So I wanted to evoke the feeling that the words we hear from the book are about a young mind in a process of discovery - and a mind that has become really perceptive about the world because of, rather than despite his autism.

Naoki’s now 25 and didn’t want to appear in the film, so it felt interesting to visualise the child he’s writing about almost as a spirit running through the film. That idea also grew from an image from Naoki’s story I’m Right Here which is at the end of the book, in which a boy dies in an accident and is unaware that he is dead. He visits his family and they can’t see him. At one point in the story he goes travels around the world as though without a body. So much of the book is about the sensation of being weighed down by a body that won’t respond to intentions - like ‘trying to control a faulty robot’ - it felt to me that this weightlessness was Naoki’s idea of Heaven.

I hope the boy evokes not only the younger Naoki, but also David Mitchell’s comment that the book was an ‘envoy’ from his own son’s world, which I think is a feeling common to many parents when they encounter the book. We are alongside the boy as he observes a world - both of nature and manmade structures - and the things that strike him in it. We were very fortunate to find Jim Fujiwara, a young nonspeaking Japanese-British autistic boy whose parents had encountered the book at the same time as their son’s diagnosis. It felt to me that Jim represented a next generation who might grow up in a world for which Naoki’s insights into autism are the norm and so a world that might be much more inclusive.

Can you talk about how you approached drawing the audience into the world of autism from a visual and auditory perspective?

Naoki remembers his childhood as one in which he faces huge barriers in communicating, and one which bombards him with distracting sounds and sights, intense memories and random associations and impulses. There are some key ideas about his sensory world that he writes about repeatedly - and these became our starting points for the way we used sound and visuals in the film. He describes a visual world in which he sees detail before the big picture and has to construct the world piece by piece, a world where sounds and sights can be beautiful and intense but also unsettling and confusing, where the attractions of light, water and repetitive movement provide some certainty and pleasure. So we used these visual ideas in the way we shot the film - often working with macro close ups in situations where we were also shooting observationally, and to keep us in the sensory world as much as possible we minimised the use of talking heads in the film.

Sound is really important in the film and we worked with sound artist Nick Ryan, who himself is synesthetic, to create a 360° Atmos sound design, starting from 360° recordings which we made in each location. There’ll be a binaural, mix so that those listening on headphones can also experience that immersive sound world.

‘Nonverbal autism’ is a bit of a misnomer because most of the group of people it describes use some speech or make sounds though not necessarily in a conventional context or in ways that enable them to express needs and opinions.

In his book Naoki goes to some lengths to describe his difficulties with speech, which he likens to a sea in which he is tossed about like a small boat in a storm. It’s as though he has two language processes going simultaneously: the words that he is able to spell out independently on a keyboard or letter board which express his sophisticated thinking about the world and the words which jump out his mouth involuntarily and might link to memories, associations or a current impulses. He describes the letter board as a tool to ‘lock down’ words and phrases which would otherwise ‘flutter away.’

Letter board or spelled communication has been highly controversial - in part because it can be subject to outside influence, and in part perhaps because aptitude with spoken language is taken to be an indicator of intelligence - and so nonspeaking individuals tend not to be believed when they spell out complex thoughts. I took this scepticism seriously, going back to some of the original research as well as more recent research around language capacity. Older quantitative studies were damning of the methods used to enable nonspeaking adults to spell to communicate, but there are now far more studies that support it than refute it. There’s also plenty of evidence that nonspeaking people possess coherent language. We know that speech is a motor-sensory facility, and that autism is closely linked with apraxia and other neuro-motor issues. There’s no question in my mind that Naoki is the author of his book - I’ve watched and filmed him type independently on a computer as well as a letter board - and when I met him he is at least as philosophically sophisticated as his books suggest. Others in the film have different capacities for communication - Ben and Emma have gone through a long process of learning to use a letter board and can now communicate clearly using it. I asked them to write pieces for the film as well as interviewing them ‘live’. What is clear to me is that we hugely underestimate the understanding of people who don’t speak.

What do you hope the film will achieve?

I hope the film is part of a shift in the way we see autistic people who don’t communicate in a neurotypical way - away from the simplistic and damaging ideas of ‘mild’ and ‘severe’, ‘high functioning’ and ‘low functioning’ and towards an understanding of the constellation of individual strengths and challenges people face. I feel that all of us can identify with some of the stars in that constellation, and that recognising this can help build solidarity with and support for people, and construct a more ‘autism friendly’ world.

ABOUT THE BOOK

THE REASON I JUMP became a New York Times and Sunday Times bestseller and has been

translated into more than 30 languages. It has sold over a million copies word-wide.

NAOKI HIGASHIDA – Writer

Naoki Higashida was born in Kimitsu, Japan in 1992. Diagnosed with severe autism when he was

five, he subsequently learned to communicate using a handmade alphabet grid and began to

write poems and short stories. At the age of thirteen he wrote The Reason I Jump, which was

published in Japan in 2007. Its English translation came out in 2013, and it has now been

published in more than thirty languages. Higashida has since published several books in Japan,

including children’s and picture books, poems, and essays. He continues to give presentations

throughout Japan about his experience of autism.

Catch THE REASON I JUMP at MINDS Film Festival’s Community Screenings this September 2023

📅Screening #1:

3 Sep 2023, Sunday at Wisma Geylang Serai, Persada Budaya, Ground Floor Level 1, 5pm - 6.30pm

📅Screening #2:

10 Sep 2023, Sunday at Tzu Chi Humanistic Youth Centre, The Great Hall, Ground Floor Level 1, 5pm - 6.30pm

Admission is FREE for the Community Screenings and seats are available on a first-come-first-served basis.