Commentary: Agnès Varda’s Lessons in Humility

Commentary: Agnès Varda’s Lessons in Humility

A Different Kind of Auteur

With the passing of the canonical French New Wave directors, retrospective readings of the movement have tended to sort its filmmakers into neat archetypes: Godard as the radical, Truffaut as the autobiographer, Demy as the romantic. Agnès Varda, however, seems to resist any categorisation.

Undoubtedly, she was an important part of the nascent French New Wave with her renowned Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962). Later in her life, however, her filmography sprawls restlessly across themes and mediums. She often tapped into her strong political conscience, releasing films like Vagabond (1985) that reflected her focus on feminist issues, or Black Panthers (1968), which documented the titular Civil Rights Movement group while she lived in the United States. Moreover, no other New Wave director has come close to Varda when it comes to documentary filmmaking, her preferred mode of storytelling in the later years of her life.

Despite the seeming impossibility of consolidation, I believe what unites her work is not thematic or stylistic consistency, but a shared ethos: humility. Through her post-2000s documentaries, Varda, in my view, redefines the auteur as a keen observer, rather than a definite authority.

The Filmmaker as Scavenger: The Gleaners and I (2000)

One of her most beloved documentaries, Gleaners is Varda’s rumination on the practice of gleaning in France, scavenging for things cast aside by society. She travels across the French countryside at first, before shifting to the streets of Paris, surveying the ways gleaning still exists today. From the urban poor who have to glean leftover crops for survival, to a Michelin 2-star chef who gleans ingredients for freshness, the film depicts the lasting vitality of a practice commonly associated with the past.

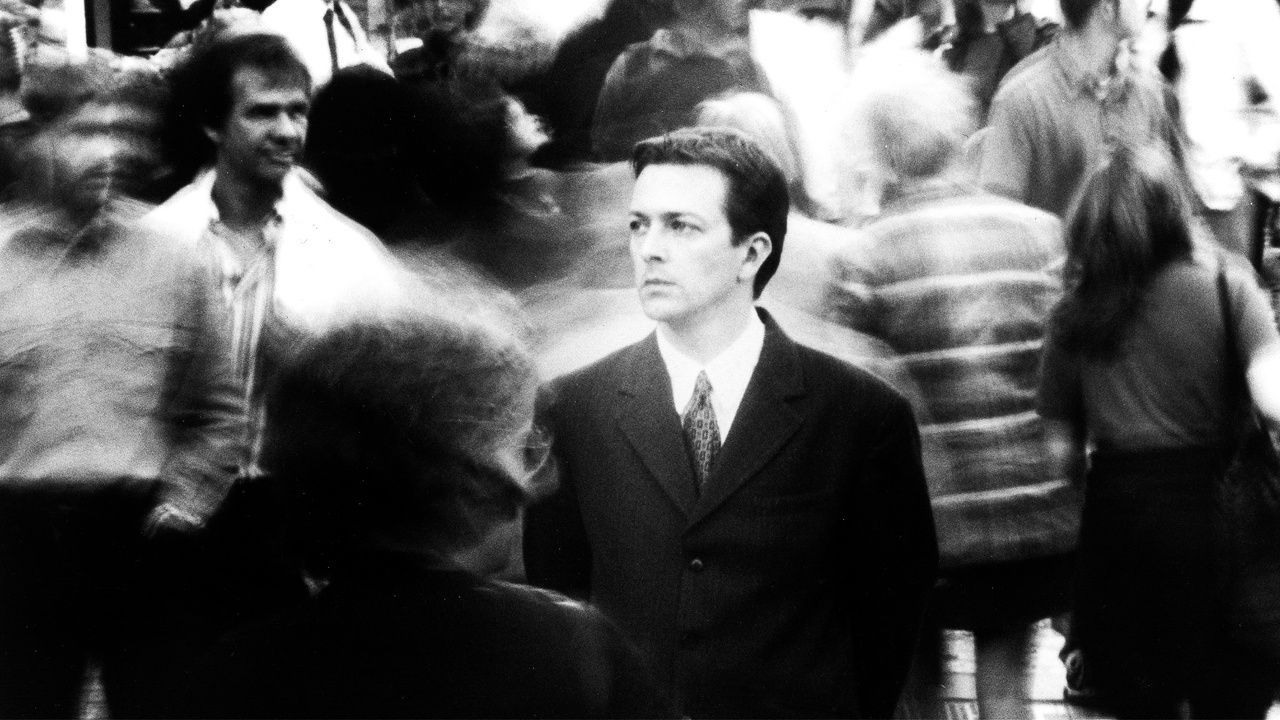

Through personal interviews with each of these groups, the film lets her subjects do all the talking, avoiding a sanctimonious or imposing tone. Even when interviewing a divorced father living in poverty, gleaning discarded potatoes just to survive, there is no swelling music, no strategic editing to build sympathy. There is only a simple prompt: “Tell me what happened to you.”

Indeed, Varda herself admits the impulse to impose a certain judgement on the poorest of these gleaners, saying that the “pitiful feeling” she felt spurred her on to make the film initially. However, she states that really getting to know these people stopped her from making any “statement”, realising that “[t]hey make the statement. They explain the subject better than anybody.[1]” Just like the subjects of her documentary, Varda is doing the act of gleaning

glimpses into different people’s lives, inherently a humble and unobtrusive vocation.

In an even bolder departure from traditional documentaries, Varda often turns the camera on herself in Gleaners. Equipped with a camcorder, she explores the power of the handheld camera in gleaning unique images that wouldn’t have otherwise been possible. Varda plays a private game with trucks along a highway, pretending to trap them with her hand in front of the camera. She marvels at the newfound possibility of “filming one hand with the other”, revealing the “horror” of age within her wrinkling skin.

Here, too, Varda documents with a humility driven by curiosity. The camera is not used as an instrument of control, but as a companion to her own wandering attention, recording moments that are incidental or even flawed. In one scene, she accidentally leaves her camcorder on, lens cap swinging in frame. Instead of cutting it out, she pairs the moment with jazzy music, letting the moment linger longer than other filmmakers might.

By turning the lens on her own hand, her own filmmaking, Varda resists placing herself above what she films, becoming just another subject she gleans from. The title of the film in its original French is perhaps the most revealing of the fact, as “Les Gleaneurs et la glaneuse” literally translates to “The Gleaners and the female gleaner”. Understanding Varda’s interest in self-interrogation, we see that she identifies as the “female gleaner”, in equal rank to those she portrays in her film.

The Collective Life: The Beaches of Agnès (2008)

In the opening scene of Beaches, Varda’s instinct for self-inquisitiveness is put on obvious display, as she narrates: “I’m playing the role of a little old lady,[...] telling her life story.” While the film is hailed as Varda’s cine-autobiography, the opening lines already signal Varda’s distrust toward the genre. She believes that theatricality underpins self-portraiture. To Agnès, it is an act of performance, rather than a veritable depiction of unfiltered truth.

“For me it’s cinema, it’s a game”, she says. In a memorable sequence, an ostensibly young Varda is playing on the beach. However, after only a few seconds, the camera pans right to reveal the real Varda, as she admits to the camera that she herself isn’t too sure “what it means to recreate [her childhood] like this”, avoiding playing into the self-dramatisation of autobiographical tools like re-enactment (unlike Truffaut, whose film

The 400 Blows

sees a feature-length fiction loosely based on his unruly childhood). She even leaves in a behind-the-scenes snippet of her speaking to the child actor playing her, playfully undercutting traditional autobiographical techniques.

This sense of play extends to a striking sequence in Varda's reconstruction of an office of her production company, Cine-Tamaris, where she builds a man-made beach in the middle of a street. The sequence is openly artificial: sand strewn haphazardly, “office workers” sporting swimwear, and Agnès begging for an “interest-free loan” from a bank.

When rain begins to fall on the second day of filming, disrupting her plans entirely, Varda does not conceal the failure. Instead, much like the lens cap in

Gleaners, she leaves the footage in, embracing the intrusion as part of the game. The rain reveals Varda’s refusal to sanitise or perfect; autobiography, for her, remains contingent, subject to chance and weather, much like her own life. What emerges is an unfettered joie de vivre that is central to Varda’s filmmaking approach, finding beauty in the unforeseen.

Having exposed the limits and artifice of self-portraiture, Varda resists centring herself for long. She quickly turns her camera on others to illuminate key aspects of her own life. These people may not have been the most important, but exist nonetheless in her life in some capacity: a tour of her childhood home becomes an interview with the house’s now-tenant, a serial collector of miniature Swiss trains.

A recollection of her start as a photographer turns into an “In Memoriam” for many of her subjects who have passed on. Even crew members who were involved in the making of

Beaches

are shown throughout the entire film, particularly in a sequence at the beginning where they help Agnès construct an assemblage of huge mirrors on a beach, signalling metaphorically that Agnès’ reflection on her life is only accomplished through the help of others.

She shows how autobiography is a convincing genre of documentary filmmaking that can be elevated not through self-indulgence, but through humility and connection with others.

The Camera in Varda’s Hands

Perhaps one of the more subtle ways in which the French New Wave has influenced cinematic culture is in directing how we think about experimentation and non-traditional filmmaking. At least personally, the word “experimentation” conjures images of rupture: jump cuts, confrontational politics, and artists bent on redefining film itself. This understanding is shaped largely by the movement’s loudest figures, whose innovations announced themselves as acts of rebellion against a cinema with which they were discontent.

Agnès Varda offers a quieter alternative. Her filmmaking is experimental, both

Gleaners

and

Beaches

being non-traditional documentary projects. But she does not seek to overhaul cinematic language. Instead, her unique style emerges from a desire to represent life as she encounters it: playful, contingent, and shared with others. The camera in her hands is not a weapon or a megaphone, but a means of looking — one guided by curiosity rather than certainty.

This curiosity is inseparable from humility. The lasting influence of her narrative work is important to her legacy, but her documentaries reveal her core as an artist. She desmystifies the artistic process from an act of creation to an act of modesty. And then, it doesn’t hurt to throw in a little playfulness, a little love. She shows us that nobody is incapable of creating, if they would just sit back and observe without judgement.

---------------------

About the author: Yiheng dedicates a significant portion of his time staring at screens. On theatre, laptop, and television screens, he can be found watching films of any kind. On his phone screen, he wages a life-long battle with his Letterboxd watchlist, perpetually trying (and failing) to clear it.

This review is published as part of *SCAPE’s Film Critics Lab: A Writing Mentorship Programme, with support from Singapore Film Society.

[1] Anderson, M. (2001). The modest gesture of the filmmaker: an interview with Agnes Varda. Cineaste, 26(4), 24-27. https://excocinema.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/06/agnes_verda_interview.pdf

[2] https://www.interviewmagazine.com/film/the-life-and-times-of-international-treasure-agnes-varda